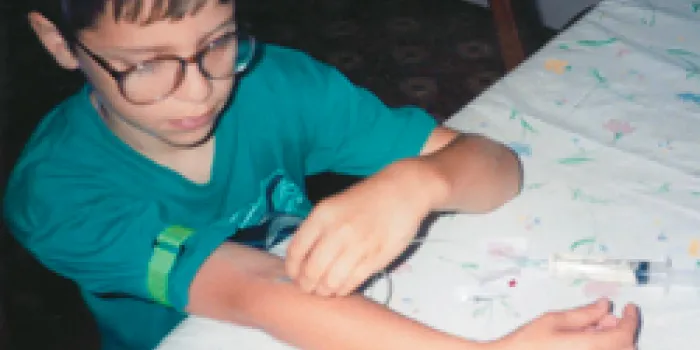

When he first started sticking himself with a needle, Nick Reiser, 24, of Howell, New Jersey, was about 7. But even before then, his parents made sure he was involved in the infusion process. “There are photos of me with a needle in my arm, helping my mom push the syringe in,” he says. After watching his older brother, Chris, self-infuse, Nick also wanted to learn. By the time he began first grade, Nick was infusing his own factor product under adult supervision.

It’s critical to start “transitioning,” or preparing children to manage their bleeding disorders, when they are very young to help them get ready to live independently by the time they turn 18, says Danna Merritt, LMSW, social work coordinator at Children’s Hospital of Michigan in Detroit. Merritt developed transition guidelines for Children’s Hospital, which later also adopted transition guidelines created by the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF). NHF’s new Steps for Living Web site will soon post an explanation of the NHF transition guidelines.

“It’s a process of letting go, of parents empowering their children to begin taking care of their own treatment and care,” Merritt says. Parents might have reservations, though. “They’re afraid their child’s not going to do it as well as they do,” Merritt says. But the effort pays off. “It’s nice to see parents feeling comfortable and confident that their child is taking over his treatment and care.” Developing responsibility is part of a child’s growth process, she says.

The Different Meanings of “Transitioning”

“Transitioning” in the bleeding disorders community can mean many things. It can be defined as the process in which the responsibility for infusions shifts from medical staff to parents, then is handed off from parents to children. It can also mean transferring medical management from parent to child over time. Or, it can refer to going from one major life stage into another, such as living with parents to heading off to college and beginning life as an independent adult. “Transitioning” is used frequently in the bleeding disorders community to describe any shifts in life that might affect care or treatment.

Transition processes continue throughout childhood as children become more independent and begin to take ownership of the management of their disorder. Important steps in the bleeding disorders community include sending a grade-schooler off to hemophilia camp, encouraging a 10-year-old to self-infuse and allowing a 14-year-old to talk alone with his or her doctor for a few minutes.

These transitions can be daunting, so it’s important for parents to remember they don’t have to do it alone. Hemophilia treatment center (HTC) staff can help families through the process. They provide direction, advice and support, says Audrey Taylor, RN, a nurse at the Hemophilia and Thrombophilia Center at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

“Our goals during any transitional process are to assist and empower our patients and caregivers,” Taylor says. Further, the team can identify support resources. For example, if a family is hesitant about doing home infusions, the HTC may be able to arrange for a nurse to make home visits to talk them through the process. HTCs can also connect parents with other families who have been through the transition.

Transitions occur gradually, Taylor emphasizes. “As your children grow up, you give them more and more responsibilities,” she says. “When you feel they are ready, accountable and mature enough to do it, then you start allowing them to not only gather the things that are needed for infusion, but start to infuse.” Children can also begin to schedule their appointments and order their factor.

Don’t wait until they are teenagers and then suddenly say, ‘OK, you’re going to do all of this,’ Taylor says. “You do it step by step.”

Involving Young Children in Infusion

When Reiser attended hemophilia camp in elementary school, he was surprised to meet other kids who needed the nurses’ help to mix factor and infuse. “A lot of them had to wait for their counselor to wake up to get their factor,” he says. “I’d just get up, go to the head nurse, and I’d do it all myself.”

Merritt encourages parents to begin attending support programs early on so they won’t feel isolated. In addition, they can get tips on how to live with a bleeding disorder. Your HTC can help you find a support group. Further, many NHF chapters have support groups, such as the Hemophilia Foundation of Michigan’s PEP—Parents Empowering Parents.

When a child reaches the age of 6 or 7, attending hemophilia camp is essential to feeling like any other kid. At camp, children with bleeding disorders are the norm. They don’t have to explain their disorder to anyone, and camp shows them they aren’t the only ones dealing with a bleeding disorder, Merritt says. Many children learn how to self-infuse at camp. The age of self-infusion depends on the maturity of the child, Taylor says. “We have some 7-year-olds who infuse who are mature and very responsible.” On the other hand, some campers aren’t ready for another year or more.

At Rush, the HTC team encourages kids and their parents to set realistic goals that will keep them on track, Taylor says. If a teenager is inconsistent with his self-infusions, for example, the HTC and the family may set a goal that within a month or six months (depending on the teen’s age and maturity level), the teenager is infusing a set amount of times without prompting.

For parents who are overfunctioning for their child in middle school, a realistic short-term goal could be allowing their child to prepare everything for the infusion, Taylor says.

More Responsibility for Teens

Reiser’s parents not only encouraged him to infuse at home, but also received permission for him to carry factor at school. “There were times when if I hadn’t been able to infuse myself, I would have had a much more severe bleed if I’d had to wait for someone to infuse me,” he says. Like the time Reiser was running in the woods with the cross-country team three miles from school and fell into a ravine. “I had brought a little knapsack with me and had the bare bones of what I needed to mix,” he said. “I sat there and infused. My teammates stayed around and helped me back to the school.”

At around age 15, children can start ordering their own factor through the HTC nurse or the factor provider. Parents may be in the background, prompting their child, which is OK, Merritt says. By 18, people with hemophilia should be keeping track of how much factor they have and know when to order more. They should also be keeping their own treatment log.

As knowledgeable and independent as Reiser was when he went away to college at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, he admits he sometimes put off calling in his factor. “There were times when I didn’t keep on top of my logs or my deliveries,” he says. “When I started running out of factor, I would pay attention. I didn’t have Mom and Dad telling me when I needed it anymore.”

Support groups for teenagers with bleeding disorders and programs such as NHF’s National Youth Leadership Institute (NYLI) also prepare teens to live on their own, says Callie Clark, a sophomore exercise science major at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. “If you find someone who’s been through the transitioning process, you’ll learn a lot more,” she says. Ask your local chapter about teen support groups.

Clark, who has moderate to severe type 1 von Willebrand disease (VWD), encourages college students to inform close friends about their condition and always wear their medical alert ID. Clark wears a blue cloth sports bracelet. “My friends know that I carry an ID card with me at all times that has a checklist of things to do if something happens, as well as the numbers for my hematologist and what kind of medicine I use. They also know where my Stimate® is stored in my dorm room.”

Reiser, who’s now working full-time at an electronics assembly plant, says one thing he could have planned better was his factor deliveries at college. He lived in a 26-story apartment building and had to sign for deliveries. When he was away at classes all day, the delivery person would wait for him. “I was never left without factor because I had a really good factor supply company,” Reiser says. “That’s really the only thing that saved me.”

As children transition through various stages, there will be mistakes, Merritt says. But those mistakes won’t turn into insurmountable obstacles if parents start the transition process early and introduce age-appropriate responsibilities as the child grows.